On April 20, Germany’s ruling CDU/CSU finally chose who it will run as the conservative candidate to succeed Chancellor Angela Merkel in Germany’s September 2021 federal election: stuffy and unpopular Armin Laschet.

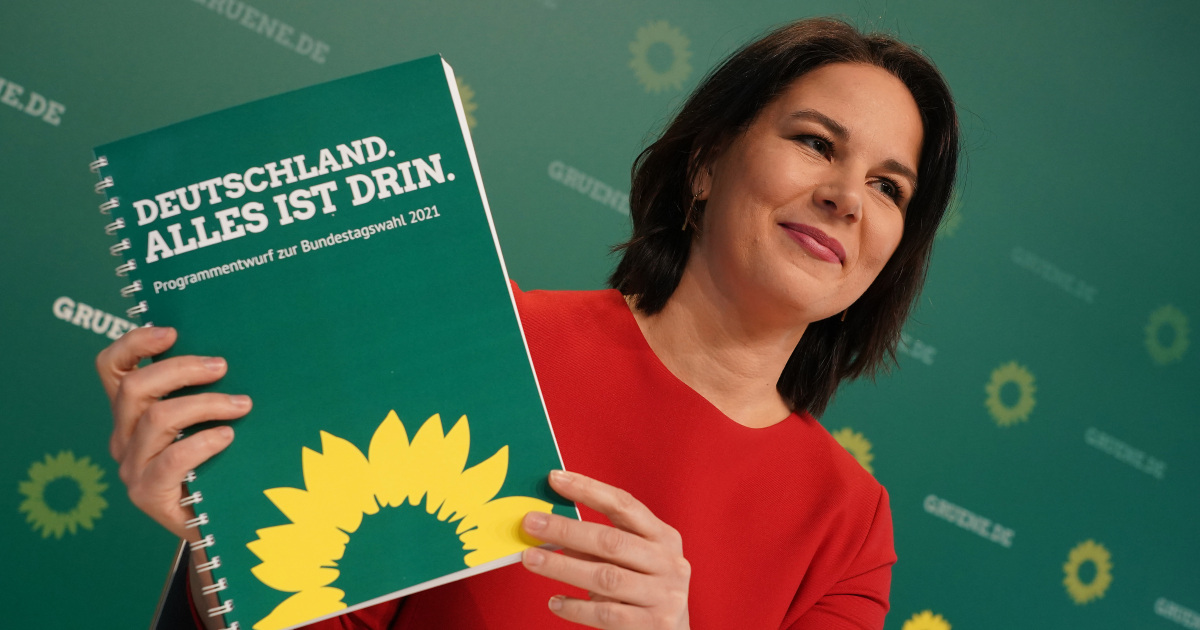

Since then that lead has solidified and the Greens have overtaken the CDU in polling averages for the first time ever, suggesting that the conservatives who have governed Germany for the last 16 years could be ousted as the strongest party in the Bundestag in September.

Moreover, seasonal labour from Central and Eastern Europe is key to Germany’s agricultural sector, and the German automotive industry has opened major factories in several central European countries such as Slovakia, Czechia, Hungary and Poland.

Germany’s CDU is the most prominent member of the pan-European European People’s Party , a key institution for transnational centre-right political cooperation in Europe.

After all, apart from Austria, where they rule in a coalition with the local EPP affiliate, Green parties in Central Europe are still not decisive actors in mainstream politics.

Poland, for example, still gets 70 percent of its energy from coal, and it is one of the only three European countries whose carbon emissions increased over the last decade.

Central European electorates’ lack of interest in climate issues coupled with the regional governments’ hostility towards Green politics would undoubtedly make it difficult for the German Greens to convince the region to take action on climate change.

If Baerbock can demonstrate the economic opportunity of the green transition to Germany’s neighbours to the East, she may be able to convince many of them to join the fight against climate change.

What that will mean for Central Europe is new political divides, but also new opportunities.