Much like baling out a flooded basement with a spoon or shoveling the driveway in the middle of a snowstorm, carbon-capture projects to date have had minimal impact at best on the bigger goal of reducing global greenhouse gas of CO2 by 2030, and up to twice that much by 2040 — enough to start making a real dent in Gulf Coast CO2 emissions.

We then took an extensive look at the federal 45Q tax credit, including how it was designed and why varying costs to capture can make some types of projects uneconomic despite 45Q, and potential legislation that could expand the size and reach of those credits.

By far the most ambitious project so far is ExxonMobil’s Houston CCS Innovation Zone, which envisions a large-scale collaboration between private industry and the government to create a platform to dramatically accelerate CCS progress.

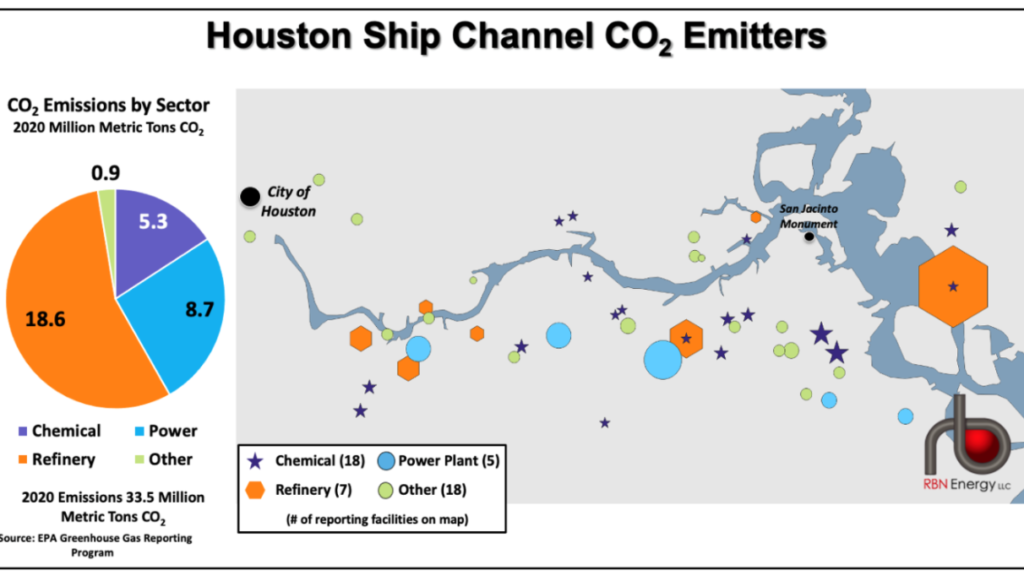

ExxonMobil has been studying whether carbon-capture hubs make sense and areas like the HSC — one of the busiest ports in the world with dozens of industrial sites in its immediate vicinity, with many others nearby — may be just the right place for initial large-scale implementation.

In this case, the captured CO2 would end up thousands of feet below the floor of the Gulf of Mexico, an area the company says can hold 500 billion MT of CO2, or about 130 years of U.S.

The big catch with a project as ambitious as this one is predictable: cost.

There’s a huge amount of money potentially on the table, so let’s look at how quickly those credits might add up for this project.

Join us for a 2-day seminar on energy market fundamentals, designed with the energy transition in mind.

Under current tax law, credits can be generated for a project’s first 12 years of operation, and the credit itself is supposed to increase with inflation after 2026, so the project would bring in more than $30 billion in tax credits.

To date, the project is known to have attracted public interest from at least 14 firms, in addition to ExxonMobil itself, and includes petrochemical producers, power plants, oil and natural gas producers and refiners.

Like other significant public-private initiatives, ExxonMobil has said the project will need significant industrial and community support, government and private-sector funding, and appropriate regulatory and legal frameworks in the areas of investment and innovation.

Lessons learned from the Houston CCS Innovation Zone could be applied in other areas of the country where there are similar concentrations of industrial facilities located near suitable CO2 storage sites.

In addition to Waits’ version, a different recording of “Way Down in the Hole” was used for each season, including versions by The Blind Boys of Alabama, The Neville Brothers, DoMaJe, and Steve Earle.

Franks Wild Years was recorded during 1987 at Universal Recording in Chicago, and The Sound Factory and Sunset Sound in Hollywood.

He moved to Los Angeles in 1972, where he worked as a songwriter before securing his first record deal with Asylum Records.