Halfway through a heavy year, the best movie so far—the one most likely to ease the load and lift you up—is “Summer of Soul.” It’s a documentary, directed by Ahmir Thompson, a drummer, a d.j., a record producer, and a founder of the Roots, best known as the house band for Jimmy Fallon.

The festival took place outdoors, in Mount Morris Park , and it was filmed, under lighting generously provided by the sun.

But we glimpse that schedule only once, in passing, and the rest of the film makes no distinction between the different days, splicing the acts together and leaving us with the impression that the crowds that mustered in the park—some three hundred thousand strong, in total—were treated to one big rolling jubilee of sweet sounds.

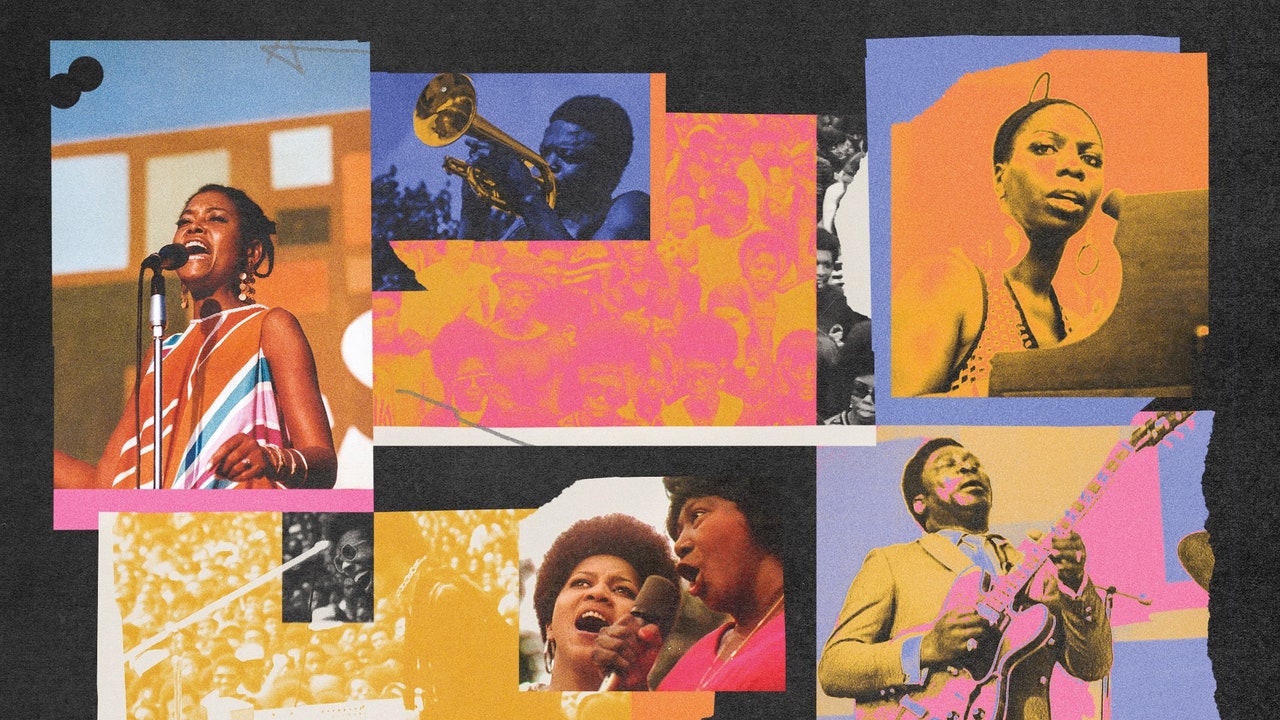

The festival’s producer, and the host of the proceedings, was Tony Lawrence, who is lauded in the film as “a hustler, in the best sense.” The outcome of his hustling was a lineup so absurdly rich, and so river-wide in its range of genres, that you want to laugh: Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson, Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, B.

Lindsay, and introduce him as “our blue-eyed soul brother.” Also visible, during a phenomenal set by Sly and the Family Stone, and easy to pick out in leopard-skin bell-bottoms, is Greg Errico.

Dorinda Drake, who was nineteen at the time, says, “That’s the summer we became free”—pause—“of our parents.” Musa Jackson recalls the aroma in the park as if it were incense: “It smelled like Afro Sheen and chicken.” He was a little kid at the festival, though not so little that he didn’t lose his heart to Marilyn McCoo, a singer with the 5th Dimension.

The cravats! The fringes! The hectic ruffs! Lawrence, as befits the master of ceremonies, sports an ever-changing cycle of outfits, including a white lace top with a carmine vest, and a shiny shirt that looks like an explosion in a host of golden daffodils.

“Summer of Soul” is one of those rare films from which you emerge saying, “My favorite part was that bit.

A year earlier, on April 4, 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Harlem had suffered riots and hours of looting, and, as Darryl Lewis suggests, “New York was trying not to have a repeat of that, in ’69.” Hence the brief but vital images of white policemen, standing calmly in the midst of Black festivalgoers, and neither making trouble nor seeking to rein it in.

What we are witnessing, in short, is not a state of bliss but a precious, precarious interlude of release and relief, before the pressures of an unequal society kicked back in.

The first movie, “The Fast and the Furious,” came out in 2001, and scholars have focussed on its emblematic scene, in which Vin Diesel’s character took his seat under the hood of a hot rod, in the space where an engine would normally be.

The character’s name is Dom Toretto.

The acting is of a soaring ineptitude; the deeper Diesel emotes, the more he resembles a man who dabbed too much wasabi on his tuna roll.

The New Yorker may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers.