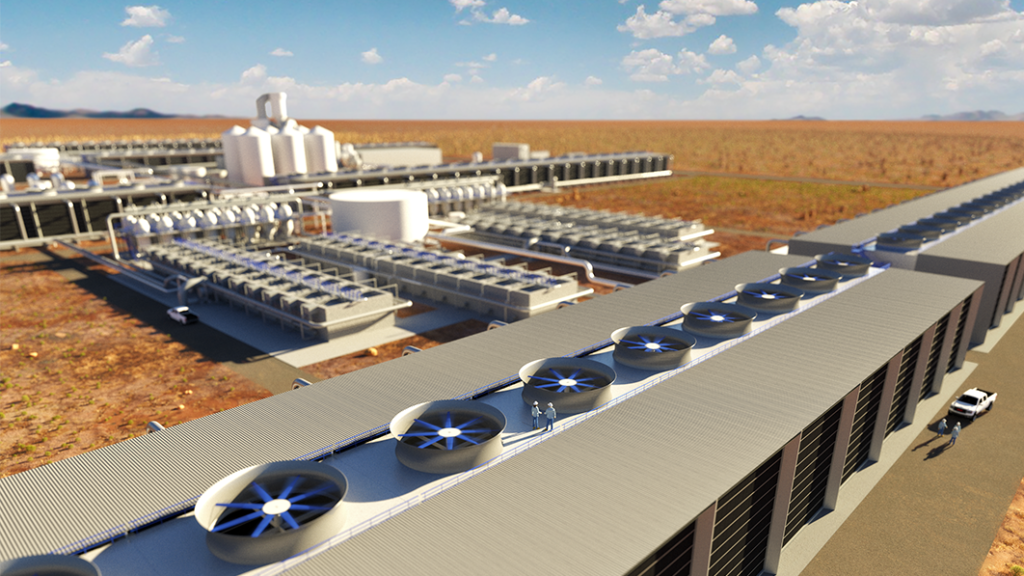

A rendering of a planned direct air capture plant in Texas that would initially pull 500,000 tons of carbon dioxide out of the air annually.

As a result, the California carbon market, which is meant to help lower the climate emissions of transportation in the state, could supply tens of millions of dollars to help extract more oil, thereby contributing more emissions.

Occidental’s plans raise one of environmental advocates’ biggest concerns about carbon removal technologies: that they will be used by oil companies to delay the far more urgent task of rapidly transitioning away from fossil fuels.

We deliver climate news to your inbox like nobody else.

Occidental says it will break ground this year in West Texas, near Odessa.

Pressed by a raft of climate disasters, regional and national governments across the globe are rushing to support carbon removal technologies.

“There’s a holy war brewing in climate politics over these kinds of technologies and whether or not they’re a tool of the oil industry,” said Danny Cullenward, the policy director at CarbonPlan, a nonprofit that analyzes the integrity of carbon removal efforts.

When climate scientists have tried to model pathways that limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, nearly all of them have required some degree of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Natural carbon removal like reforestation will need to play a large role, and there are a suite of other techniques, like converting waste biomass into charcoal that can be mixed into the soil or tinkering with seawater to enhance its absorption of CO2.

Still, the largest existing direct air capture plant, built by the Swiss start-up Climeworks, which has not partnered with oil companies, removes only 4,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year.

The hope, or prayer, is that capacity could rise sharply in the following two decades.

California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, or LCFS, aims to lower the state’s transportation emissions by setting a statewide benchmark for the carbon intensity of its fuels.

Since 2018, oil refineries and biofuels plants have also been allowed to install carbon capture equipment to effectively lower the carbon intensity of their fuels.

Robert Zeller, vice president of technology at Occidental’s low-carbon business, said in an interview last month that his company was working with regulators in California to gain access to the LCFS market for the Texas direct air capture plant.

California’s equal treatment of carbon dioxide used for so-called “enhanced oil recovery” and that which is just stored is particularly problematic, Cullenward said, because each credit sold in the state represents an additional volume of gasoline or diesel that is burned in its cars and trucks.

Jeremy Martin, director of fuels policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said he thinks the state should “adjust” how it treats enhanced oil recovery.

At the CERAweek energy conference last month in Houston, a couple of dozen men and women hailing mostly from the financial and energy sectors watched as Occidental unveiled a holographic animation of its direct air capture plant.

The company has licensed technology from Carbon Engineering, a Canadian direct air capture start-up, that passes air over a mineral-laced liquid, which draws out the carbon.

The plant would be powered with a combination of renewable energy, generated specifically for its operation, and natural gas.

The company’s oil fields in the Permian Basin, beneath Texas and New Mexico, still hold about 2 billion barrels of oil, she said, but in order to pump the oil to the surface, Occidental must inject carbon dioxide into the reservoir to increase its pressure.

Technologies to extract carbon dioxide from exhaust plumes had been used by industry for decades, and more recently, some scientists and companies had begun experimenting with ways to pull the gas straight from the air.

And in California, state regulators began allowing carbon capture and direct air capture plants to begin accessing its low-carbon fuels market, even if they were located outside the state.

Both changes drew lobbying and support from Occidental and other oil companies.

Over time, nearly all of the carbon dioxide injected for enhanced oil recovery can remain underground if it is monitored properly, and experts say it is possible to store more carbon dioxide than is emitted by the oil that’s produced.

Over the last three weeks, Occidental has announced a flurry of activity around its direct air capture plans.

One week later, Occidental announced a deal with a South Korean refiner to buy up to 200,000 barrels of oil squeezed out of the ground with CO2 captured by the Texas plant.

His work has won numerous awards, including from the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Society of American Business Editors and Writers, and has appeared in more than a dozen publications, including The Washington Post, Businessweek, The Nation, Fast Company and The New York Times.

Every day or once a week, our original stories and digest of the web’s top headlines deliver the full story, for free.