The running time of the new Paul Thomas Anderson movie, “Licorice Pizza,” is a hundred and thirty-three minutes, and much of that time is occupied with running.

Remember the explosive scene in “The Master” , when Joaquin Phoenix burst through a door and set off across a plowed and misty field, at full tilt, with the camera hurrying to keep up.

He certainly acts older—instantly asking her out and, when she shows up, ordering dinner and plying her with questions such as “What are your plans? What’s your future look like?” He sounds like a patriarch, interviewing a prospective daughter-in-law.

How would we react to “Licorice Pizza” if the main roles were reversed, and Alana was the minor? As we now react, perhaps, to a half-forgotten movie of 1973, Clint Eastwood’s “Breezy,” which chronicles the alliance of a young hippie , it’s both a shock and a relief to find that, by and large, “Licorice Pizza” keeps the carnal peace.

Rather, it’s shaggy with happenings—with the weird, one-off events that tend to crop up during adolescence, and to grow funnier, and taller, in the telling.

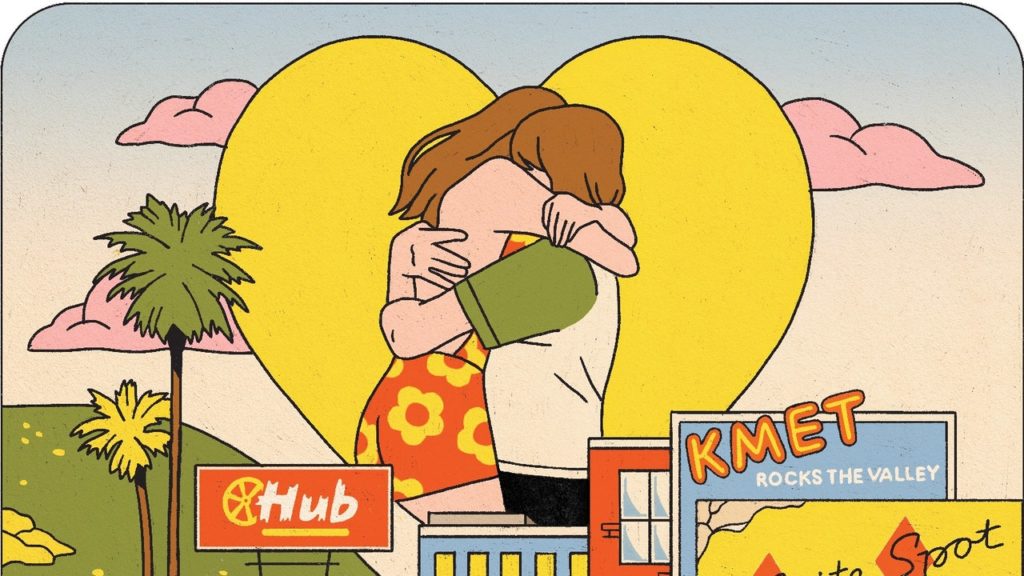

Busy and thronging, rammed with cameos and comic turns, and sewn together with songs , “Licorice Pizza” nonetheless hangs on the rapport—more than a friendship, less than a love story, and sometimes a power struggle—between Gary and Alana.

Without such candor, the film wouldn’t spill over with life as freely as it does, and nothing is fiercer or fonder than the insult that she flings at one of her sisters: “You’re always thinking things, you thinker.” There’s no answer to that.

It’s set in the nineteen-eighties—starting, specifically, at the point in 1984 when Diego Maradona, widely worshipped as the best soccer player on Earth, is poised to sign for S.S.C.

The heavenly shots of Naples, viewed from the bay and glittering in the sun, are impossible to resist, and, when Fabietto’s aunt Patrizia , whom he adores, turns and looks at him, in silence, framed by olive trees and lulled in late-afternoon light, we know that this moment of epiphany is one he will not forget.

Besides Patrizia, we meet Fabietto’s brother, an aspiring actor named Marchino Also part of the clan: a tetchy uncle who asks, “When did you all become such disappointments?,” plus a foulmouthed elder who wears a fur coat in summer and holds a dripping burrata in her hands, munching it like a peach.

Look at Fabietto’s father, jabbing the buttons on the TV with a stick and announcing, “I’m a Communist,” as if that excused his lazy reluctance to buy a remote; or strolling through the nineteenth-century elegance of the Galleria Umberto, and murmuring, “See that column? I spent the entire war leaning against it.” That’s my favorite line of dialogue this year, and it links Sorrentino’s film to the everyday joys of “Licorice Pizza.” As winter impends, we are lucky to have this pair of balmy tales.

The New Yorker may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers.