Physicists and soil scientists at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have teamed up to develop a new method for finding carbon stored in the soil by plants and microbes.

Microbes in the soil then take this carbon and turn it into organic matter that can persist for decades, centuries, or longer.

Human land use for agriculture has depleted organic matter in the soil, resulting in an enormous soil carbon deficit that also contributes to climate change.

But before we can harness them to help manage atmospheric carbon, we need to accurately measure how much carbon is already locked in the soil through plant-microbial interactions, or other management strategies.

“We have a major limitation in understanding and quantifying how carbon enters and persists in soil because of the way that we measure it,” said Eoin Brodie, a Berkeley Lab scientist.

Will Larsen and Arun Persaud at the neutron test facility of the Fusion Science and Ion Beam Technology Program in the Accelerator Technology & Applied Physics Division, configuring the alpha particle detector.

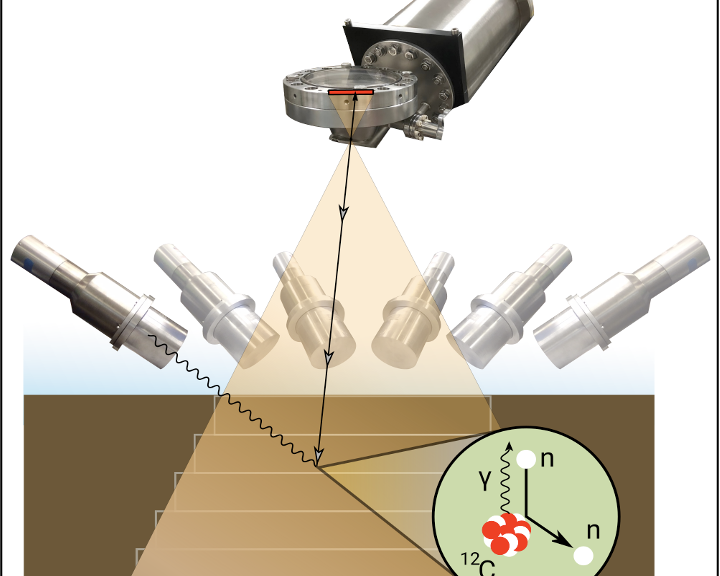

Then a detector senses the faint response of the carbon and other elements in the soil to the neutrons, allowing it to map the distribution of different elements within the soil to a resolution of about five centimeters.

“What really excites me about this neutron imaging approach is that it lets us effectively and accurately image the carbon distributions in soils at the scales that carbon accounting needs to happen at,” added Brodie.

Right now the project is just emerging from the lab, and Persaud, Brodie, and their colleagues are about to test it in real soils in an outdoor system soon.

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 14 Nobel Prizes.