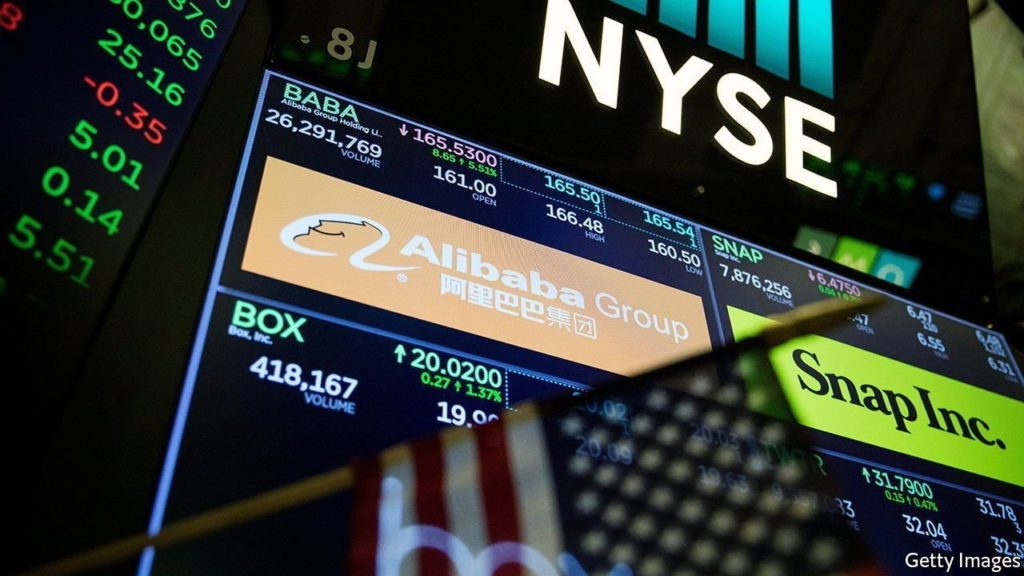

EVER SINCE the start of the trade war between America and China, investors, politicians and businesses have been trying to gauge how far and how fast the world’s two biggest economies will decouple from each other.

It is likely that all the $2.1trn of other mainland Chinese firms’ shares traded in the Big Apple will eventually follow suit, with the approval of the Chinese Communist Party.

When the first Chinese firm went public in New York in 1993, cross-border listings were endorsed by authorities, which acknowledged that American markets offered a lower cost of capital, more sophisticated investors and better corporate governance.

It is said to be under pressure from the Cyberspace Administration of China to shift its listing, probably to Hong Kong, which is increasingly under the direct supervision of the mainland government.

Even as Xi Jinping, China’s president, unleashed a war on big tech and tycoons under the banner of “common prosperity”, more than $100bn flowed into mainland markets in the first nine months of 2021.

China’s domestic markets are still unfamiliar territory in some ways, and foreign investors may not commit as much capital because they are worried about currency controls, unfair treatment at the hands of regulators and the risk of expropriation.

The more it punishes Chinese firms, whether those listed in America or those that buy American high-tech components, the more China develops its own capabilities, undermining American pre-eminence and creating alternatives for third countries to use.

But the most glaring dependence of all that China has is on America’s currency, which is used for most cross-border payments and which exposes it to sanctions and the threat of exclusion.