The very first thing we see in 1971’s Klute, the first of that string of masterful thrillers, is a tape recorder, and the opening credits roll over more images of that device as it eerily emits intimate lines of dialogue.

By All the President’s Men, the trilogy’s final entry, the threat has escalated to the highest levels of society, as our heroes realize they’re under surveillance by no less than the United States government.

“If you look at the ’70s, there was a lot of mistrust in systems, government, and corporations in society,” Mr. Robot creator Sam Esmail, a Pakula devotee whose work is heavily influenced by the Paranoia Trilogy, tells EW.

“Pakula saw the seeds of all of this in that era,” says Jon Boorstin, who worked closely with the filmmaker as an all-purpose assistant on The Parallax View and All the President’s Men.

You can trace the roots of Pakula’s work back to 1940s film noir, which Pakula himself cited as an influence on his paranoia films, and to the shifting tides of anxiety in the country across the Cold War era.

As the 1960s wore on, that cynicism deepened further, and the ’70s paranoid thriller soon emerged in full bloom.

Klute, for example, seems in hindsight to anticipate Watergate, and the anxieties around surveillance that would grow only more potent in the following decades.

Klute also evokes fear around predatory men and a system that fails to protect women in ways that echo forward through the years.

Promising Young Woman, he adds, could be a blueprint for “a #MeToo paranoid thriller” down the line.

Beatty’s character discovers a labyrinthine apparatus designed to execute assassinations and pin them on “lone gunman” scapegoats, a system that apparently goes, in paranoid parlance, all the way to the top.

“I hate to even use this analogy, but The Parallax View is almost Q-like in its idea that whatever is going on at the upper levels of government, it’s not what you think,” Harris says, referring to the far-right QAnon conspiracy theory.

It’s a theme that clearly remains potent: Another recent Oscar contender, Judas and the Black Messiah, returned to the political territory of ’70s thrillers, becoming one of the first major studio films to deal with the FBI’s COINTELPRO program.

Judas director Shaka King has spoken about how he approached the film through the lens of a thriller: “I recognized that the only way to get a movie like this made was to couch it in a genre,” he told The Atlantic.

“That movie has a lot of Pakula in it, I think,” Boorstin says.

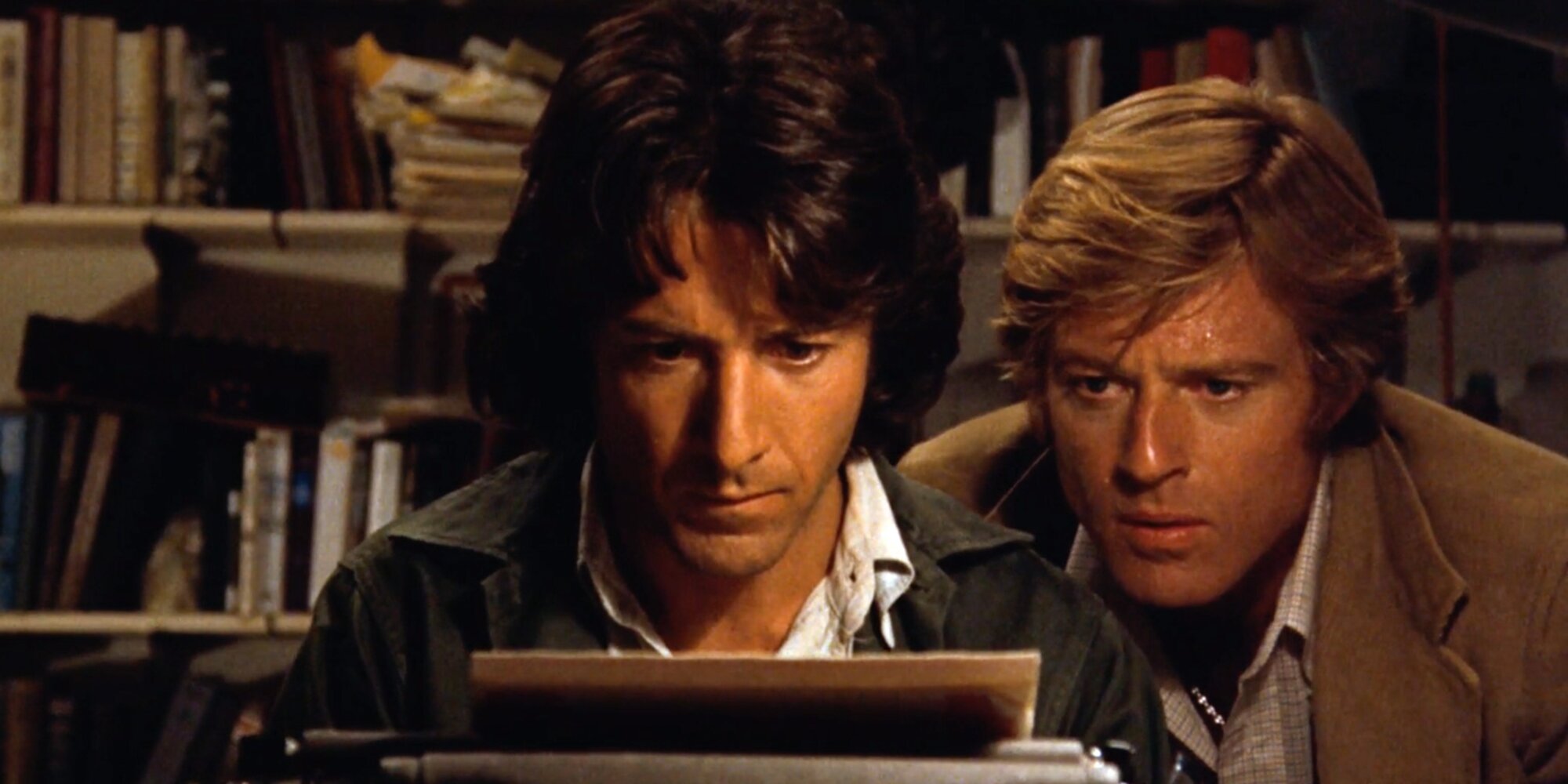

All the President’s Men, of course, dramatizes the real-life exposure of the Watergate scandal, as Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward work doggedly to uncover the story.

Near the end of the film, when Woodward meets with his anonymous government source Deep Throat , he’s told that the conspiracy is vaster than he could have imagined, that “it involves the entire U.S.

Says Boorstin, “I miss having the old clarity of values that these things were wrong, and you couldn’t get away with it, and the general feeling that if you got the truth out, it made a difference, which is what we sort of felt at the time.

Perhaps that’s why, as Esmail says, “paranoid conspiracy thrillers are coming back into vogue.

The genre also seems to be evolving in expansive ways.

He also points to Kitty Green’s chilling 2020 indie The Assistant, about an underling to a Weinstein-esque film executive: “I thought that movie did an excellent job of creating an unsettling mood that took you into the protagonist’s head.

You come out of it with a sort of catharsis of understanding something that’s been going on your lifetime a little bit more, through another person’s point of view.