March 16th felt like spring in Chernihiv, a city in northern Ukraine.

The result is to cripple health care, scaring people from coming to a clinic if they need help.

In addition, the shock wave shattered windows across all nine floors of the building, showering everything with broken glass.

“We were trying to find all the wounded to prioritize them,” he says, “to render them necessary aid” — including sedatives.

Tetiana Lebedieva, deputy director of the Chernihiv Health Department, stepped into what had become City Hospital No.

This place of healing, she says, had employed over 300 physicians of more than 30 specialties, including an especially strong cardiac surgery department.

“The decision was taken very quickly,” Lebedieva says, “to move all the patients who were able to walk, to move them to the underground floors,” which had sustained less damage from the shelling.

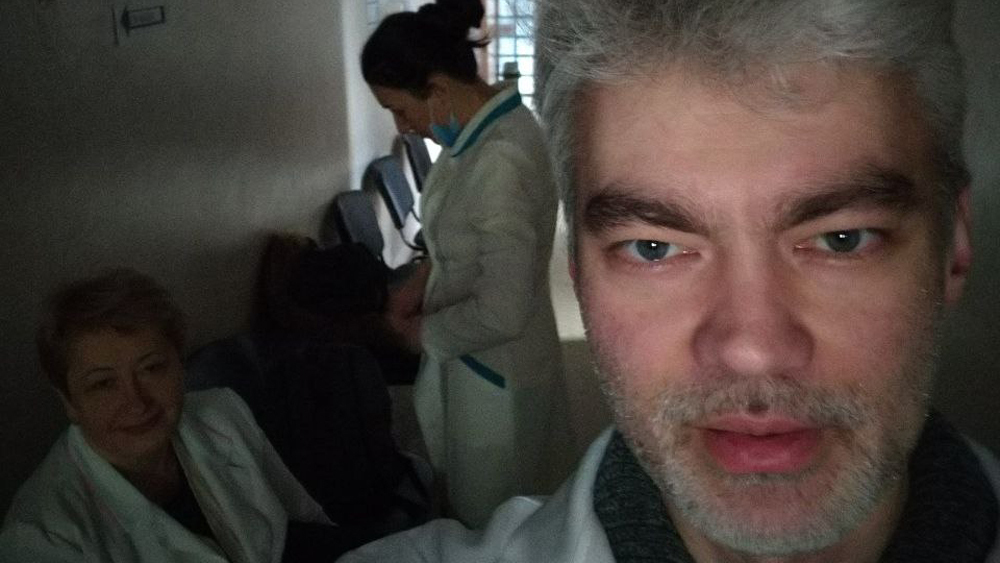

This is what Tetiana Lebedieva had come to document, with her eyes and her phone — the latest in a string of attacks on health infrastructure.

Within city limits, all seven municipal hospitals are now damaged and only three remain partially open, including City Hospital No.

Medical personnel across the city describe the difficulties they’ve witnessed.

Oksana Lohvinchuk, medical director of that same district hospital, says that a nurse in a nearby village called her to say farewell.

From the start of the war until the publication of this article on April 7, the World Health Organization has reported 103 assaults on Ukrainian health facilities.

Pavlo Kovtonyuk is the former deputy minister of health in Ukraine, and he’s now working with the Ukrainian Health Care Center, a group he co-founded, to document attacks on health facilities as possible evidence of war crimes.

The hospital moved all of its work to the ground floor, transforming it into an emergency triage center, mostly for the wounded.

More than half of Chernihiv’s population of not quite 300,000 people has fled, but numerous medical personnel have stayed behind to help at City Hospital No.

Lebedieva observed that Ryzhenko has hands that are “capable of big miracles.” But once the war broke out, the pediatric surgeon became a full-time volunteer trauma surgeon.

He says when the explosions paused, staff — holed up in the basement — streamed out of the hospital with gurneys and tourniquets, ferrying new patients inside where the triage begins anew.

Ryzhenko and the other surgeons have done the best they can, running their operating equipment on generators.

“In the night, the temperature was minus,” he says.

Even in these grim times, Vladyslav Kukhar, the director of City Hospital No.

“It demands more effort these days, but the patients get better,” he says.