Then, the energy crisis struck, leaving Asia and Europe scrambling for fossil fuels, forcing China to double down on coal, and giving climate laggards another excuse not to engage.

Developing nations say rich countries wrecked the planet as they industrialized, and it’s now unfair they’re thwarting others’ economic progress — and failing to provide enough cash to help poor countries adjust.

Here is a guide to what’s shaping up to be a fraught two weeks of talks.

If the G-20 — which includes major emitters China and India — can’t make progress, it will bode badly for the talks in Glasgow, where the leaders are heading straight from Rome on Sunday night.

Some delegates will be there in person, some will dial in from home, and there will be strict rules on masks, numbers allowed in negotiating rooms, and Covid testing.

Under the landmark Paris Agreement of 2015, countries have to regularly review their pollution-reduction pledges in order to ensure the world stays on track to limit the rise in temperature to close to 1.5 degree Celsius.

US climate envoy John Kerry has already acknowledged the plans probably won’t be enough, and one aim of Glasgow is to make sure countries keep coming back with improved goals.

The UK hosts describe the aims for this COP as “coal, cars, cash and trees.” That means ending the use of the most polluting fossil fuel; phasing out the internal combustion engine; raising cash to help developing countries transition to cleaner energy and protect against the ravages of climate change; and reversing deforestation.

The UK presidency has set a target for the meeting to consign coal to history — and has been pushing for the goal at G-7 and G-20 meetings this year — with mixed success so far.

More than a decade ago, developed nations pledged that by 2020 they will raise $100 billion per year to help developing nations transition to cleaner energy.

“We absolutely need to meet the $100 billion,” says Tina Stege, climate envoy for the Marshall Islands.

Last month, Biden doubled the latest US pledge to $11.4 billion annually beginning in 2024, but that still has to be approved by Congress, and activists argue it doesn’t come close to the US’s fair share for the fund.

3 for finance day, with a focus on how to green the global financial system and funnel money away from polluting industries and into cleaner ones.

The buzzword to watch is Article Six — referring to those lines in the Paris deal that paved the way for a global carbon market but are so complex and controversial that they are yet to be finalized.

The basic idea is to match carbon-sucking projects that reduce pollution with counterparties who need to reduce emissions, via a market of so-called offsets, which could be worth as much as $100 billion in 2030, according to some estimates.

There are two big sticking points: one is the need to avoid double counting, the other is how to deal with old credits from a now-defunct system launched way back in 1997 under the Kyoto Protocol.

A clear win on just one issue will probably count as success, and it’s possible there will be progress that can be built on down the line.

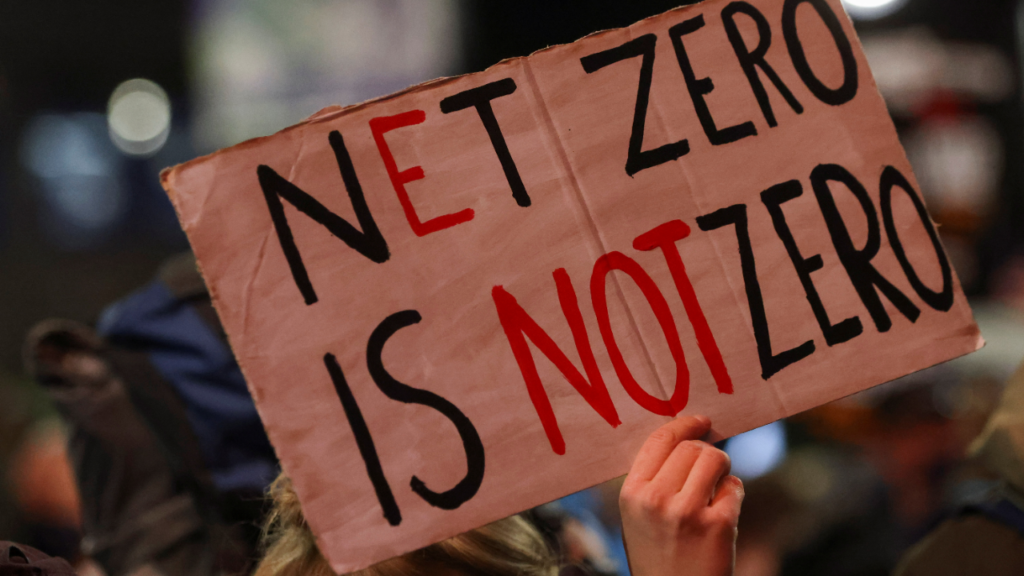

But as the main goals of ending coal and getting a net-zero commitment slip out of reach, work is under way to hatch a series of side deals that would go some way to salvaging the talks — or at least saving face.